Meaningful efforts to engage in this work at the provincial and federal level are emerging slowly within settler populations. “Indigenous people and the Canadian government are only in their infancy in terms of healing this catastrophic attempt at cultural genocide so it is understandable that cooperation in the development of educational resources for a Native Studies curriculum is also in its infancy. This is where the educational system came from, and there are many challenges that lie ahead” (Ryan, Van Every, Steele, McDonald in Kulnieks, Longboat & Young, 2013, p. 24). Discussions regarding the ongoing impacts of colonialism that continue to negatively disadvantage Indigenous communities and building and sustaining respectful treaty relationships have only recently begun to emerge in the Early Years sector. As a result, many educators who did not have opportunities for these kinds of conversations feel unprepared to tackle them with their own students. Due to the avoidance of conversations about colonialism, several generations of Canadians have been misinformed or have completely missed learning their country’s violent history. These are hard lessons to learn as an adult, and those who learn it later in life struggle with knowing how to catch up in their understandings of Indigenous history in order to set the record straight with the next generation. Through a more direct approach to learning about Indigenous history in Canada, and increased exposure to Indigenous knowledge, children could be challenged to consider their role as treaty partners at a younger age. This learning would support children to develop respect and understanding of the importance of tackling the complex issues in the anthropocene together, using multiple worldviews.

While mainstream channels are increasingly engaging with efforts toward reconciliation, this is not new work for Indigenous people. One of the most extensive publications on this subject, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, was published in 1996 and “was the result of a huge mobilization of Canadian scholars and public servants in an effort to unravel the effects of generations of exploitation, violence, marginalization, powerlessness, and enforced cultural imperialism on Aboriginal knowledge and peoples.” While it proposes that Canada “must dispense with all notions of superiority, assimilation, and subordination and develop a new relationship with Aboriginal peoples based on sharing, mutual recognition, respect, and responsibility… the government of Canada has done little to acknowledge its contents or its value” (Battiste, 2013, p. 26). Even today, the main province-wide guiding document for K-12 teachers in understanding Indigenous issues in their classroom, the Ontario First Nations Metis and Inuit Policy Framework, lacks the necessary acknowledgement of our country’s history. This document is meant to guide educators working within the public education system, and “although this history is hinted at in several ways in the Policy Framework, colonialism is never named” (McFarlane, 2018, p. 2018). Educators must instead take their learning into their own hands and spend time reviewing the foundational documents that have been written about Indigenous education (such as Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and others mentioned in a podcast series by Ryan McMahon) and find ways to move these ideas forward in their own classrooms and communities. In doing this work, they can become active participants in supporting causes of Indigenous people in their efforts to reclaim what was originally theirs and what was violently stolen from them, and become vocal members of change and educational reform.

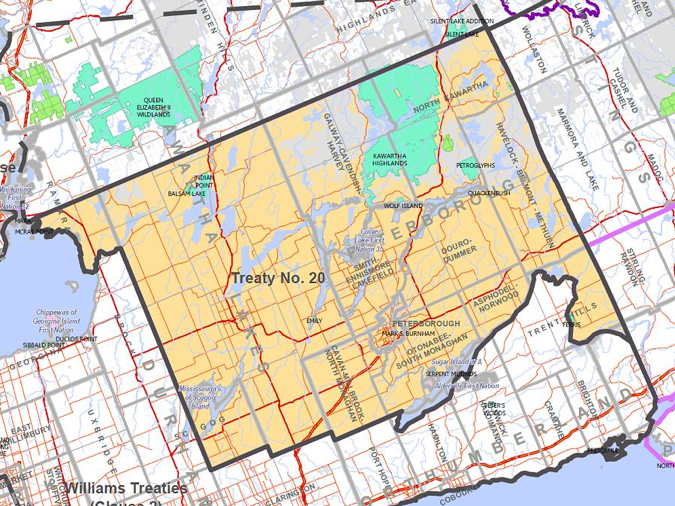

In a small attempt to start this conversation in my own work, I can start to explain the complexity of this, especially since treaties were sometimes imposed on existing treaties. So while most of my organization operates within Williams Treaty territory, one section is also part of Treaty 20 territory, which overlaps with Williams Treaty. Phil Abbott explained to me that Indigenous nations had a long history of cross-nation treaties long before settlers arrived, and since treaties were often verbal agreements, and based on previous ones, there can often be misunderstandings about their interpretation. Written documents serve as a colonial framework and didn’t always represent the agreement as it was understood by the signatories. He also suggests that “settlers have focused on the rights not the responsibilities” (Abbott, 2017) so we now find ourselves making sense of something that happened a long time ago. Working with Elders like Doug Williams, Abbott’s pending publication is one helpful example of understanding local history that brings perspective to the ways in which treaties have not been upheld in this particular place.

Below is a map outlining Treaty 20 territory, where I live and work:

Recognizing and upholding treaty relationships is not rocket science. Educators each have a role to play in moving forward respectful relationships between Indigenous and Settler populations in order to live into treaty. While it can feel overwhelming to try and learn about this complicated history, especially if it is new information, by treating this work as foundational to our role as educators, we can prevent the same thing from happening to the next generation of children. By teaching them about the history of our country starting at a younger age, they will be better prepared to carry out respectful treaty relationships into the future generations.